The S&P 500 just confirmed a Bear market; What investors should know

The bear is back.

The S&P 500 on Monday confirmed what many investors have been saying for months: The large-cap benchmark is in the grips of a bear market.

Stocks suffered sharp losses Monday after major benchmarks saw their worst week since January. Much of the weakness was attributed to the Friday reading of the May consumer-price index, which surged to 8.6% year-over-year — a 40-year high. Investors fear the Federal Reserve will have to raise rates even more aggressively than already expected, risking recession in their effort to tame inflation.

The S&P 500 SPX, -3.88% fell 151.23 points, or 3.9%, to end at 3,749.63, down 21.8% from its Jan. 3 record close and surpassing the 20% pullback threshold traditionally used to define a bear market.

Need to Know: The S&P 500 is clinging to a key support level after Friday’s meltdown, here’s what happens if that fails

The S&P 500 briefly traded below the bear-market threshold in May, but didn’t close below it. Stocks subsequently bounced, but the rebound has since given way as recession fears have increased.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -2.79% finished with a loss of 876.05 points, or 2.8%, to finish at 30,516.74, after dropping more than 1,000 points at its session low. A close below 29,439.72 would put the blue-chip gauge into a bear market. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite COMP, -4.68%, which slumped into a bear market earlier this year, dropped 4.7% on Monday, leaving it nearly 33% below its Nov. 19, 2021, record close.

To be sure, many investors and analysts see a 20% pullback as an overly formal if not outdated metric, arguing that stocks have long been behaving in bearlike fashion.

Note that the S&P 500’s finish on Monday means the start of the bear market is backdated the Jan. 3 peak. A bear market is declared over once the S&P 500 has risen 20% from a low.

How have stocks behaved once a bear market has been confirmed? History shows that usually more pain was in store.

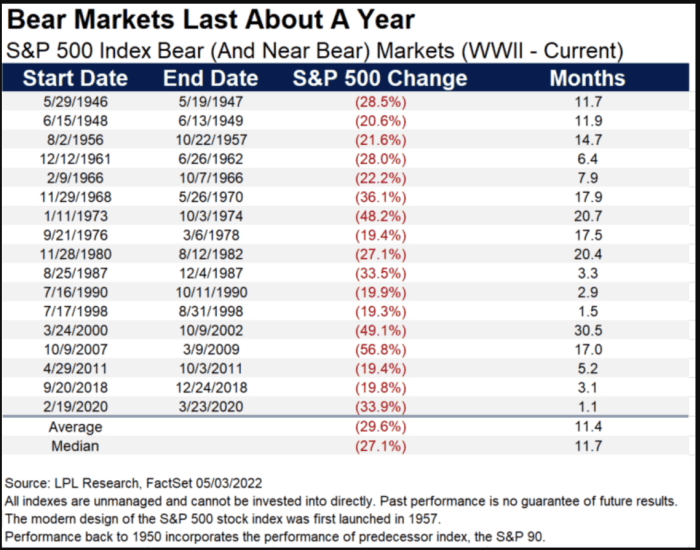

There have been 17 bear — or near-bear— markets since World War II, said Ryan Detrick, chief market strategist for LPL Financial, in a May note. Generally speaking, the S&P 500 has fallen further once a bear market begins. And, he said, bear markets have, on average, lasted about a year, producing an average peak-to-trough decline of just shy of 30%. (see table below).

Beyond the averages, there’s a lot of variability in the length and depth of past bear markets. The steepest fall, a peak-to-trough decline of nearly 57%, occurred in the 17 months that marked the 17-month bear market that accompanied the 2007-2009 financial crisis. The longest was a 48.2% drop that ran for nearly 21 months in 1973-74. The shortest was the nearly 34% drop that took place over just 23 trading sessions as the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic sparked a global rout that bottomed out on March 23, 2020, and marked the start of the current bull market.

JP Morgan, Goldman economists now expect Fed to raise rates by 75 basis points on Wednesday

Economists at JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs said in client notes Monday that they now expect the Federal Reserve to raise its policy rate by 75 basis points on Wednesday.

JP Morgan JPM, -2.98% economist Michael Feroli pointed to the “startling rise in longer-term inflation expectations” in a Friday consumer sentiment report and a Wall Street Journal article on Monday suggesting that Fed officials wouldn’t be “constrained by their previous guidance” of a 50-basis-point increase as reasons for his revised forecast.

Of the WSJ article, Feroli also said “one might wonder whether the true surprise would actually be hiking 100bp, something we think is a non-trivial risk,” in a Monday client note.

A 100-basis-point hike would increase the fed-funds rate by 1% from its current 0.75% to 1% target range.

“Our best guess,” Goldman GS, -1.29% economists wrote, is “the article is a hint from the Fed leadership that a 75bp rate hike is coming at the June FOMC meeting on Wednesday,” in a Monday client note.

Market participants largely had been expecting a 50-basis-point hike by the Fed this week. Since Friday’s inflation reading, however, stocks have tumbled, landing the S&P 500 index SPX, -3.88% in a bear market on Monday.

Read: The S&P 500 just confirmed a bear market: What investors need to know

Turmoil also took the 10-year Treasury TMUBMUSD10Y, 3.327% up to 3.371% on Monday, its highest since April 2011, according to Dow Jones Market Data. Bond prices and yields move in opposite directions.

“The Fed has to rein in demand by reducing excess liquidity,” said Robert Pavlik, senior portfolio manager at Dakota Wealth Management, by phone. While he noted the central bank can’t control supply imbalances, it can control demand by raising rates, which makes it more expensive for households to spend on credit.

“That’s where my argument for a 1% rate hike this week comes in,” Pavlik said. “Just rip the Band-Aid off and do it.”

Krishna Guha, a strategist at Evercore ISI, said the WSJ report “de facto tees up a 75 [basis point hike] this week,” but also that it isn’t “what we think is optimal policy,” nor “good for markets.”

JP Morgan’s Feroli now sees the terminal fed-funds rate in a range of 3.25% to 3.50% by early next year, whereas Goldman economists expect to see that range by the end of December.

Barclays economists on Friday were quicker to call for a 75-basis-point rate hike, saying that an aggressive move in June would provide the Fed its “biggest bang for its buck.”

Leave a Reply